Buying Beads in Tunisia

by Barbara on Dec.05, 2010, under Unpublished Writing

Tunisia is situated at the northern most bulge of Africa, it thrusts out toward Sicily and marks the division between the eastern and western Mediterranean Sea. It is bordered on the west by Algeria and by Libya in the south, with an area of 164,000 square kilometres. It is a country with disparate geography: coastal plains on the east rise to an escarpment where vast olive groves extend forever, in the north Atlas shrugs and holds the world on his shoulders and in the south, the vast sweep of sand that is the Sahara. In May 2010 I step onto a British Airways aeroplane and fly to this place of mystery, flat white architecture and lost landscape; a land of mythology. I am on a bead buying business expedition with Tamiko Sher.

We step out of the plane into warm air. Tunis, the capital of Tunisia, immediately all I see is a blue and white town; crumbling and old, new that reflects the hard sunlight. The architecture is mostly Arabic; flat roofs, small windows to keep the shade indoors, houses built around a courtyard, which serves as a family work space, private, far from strange eyes. We cannot drive to the hotel where we are to stay for it is in the middle of the medina; the older, more classical part of the city. This area is dominated by the main mosque and the public baths; the souk in the middle is surrounded by small streets and shops, each one selling something different: couscous and olive oil, dates and gold, the smell of spiced perfume on Chinese T-shirts.

The taxi stops on the outside of this scramble of streets; we wheel out bags over cobbled stones to the entrance of the hotel, past an old man who carves a wooden stick, a branch of dates lies next to him. The hotel, Dar Bel Hadj, is old, the home of someone wealthy a long time ago, now it is a house for many to stay in, for a night or two, or, as the city is beguiling, maybe more. I stand on the red and blue woven carpets and open a shuttered window, in a narrow street children shout as they play with a wire wheel, a dark eyed young man sharpens his knives on an old knife grinder and the echoes of karaoke come to me from the bar next door; the old and the new, they blend and fuse, they are of one space, there is no silence, people breathe. In the evening the dark ushers in the quiet, the streets are empty, all have returned to their homes for a night of rest. We walk to a restaurant, Dar El Jeld, according to directions that we are given, the narrow streets wind, turn right does not mean at a distinct road turn right for there are myriad right turns, we walk further, along the walls men in black leather jackets stand silent, they smoke they look at us as we pass, lonely cats slip in and out of sewers, the ghost of a fish bone in their mouths. The silent stares make me fearful, for now there are only eyes, a glassy gaze in a soundless street. At last we find the place, the entrance is subdued, a small light above the sign is the only indication that it is there. Inside we are shown to a table, the room is large and high, above us is an open corridor from which rooms lead, a man sits and plays the sitar, a piano like instrument that does not have keys instead it has chimes which are gently touched so as to make the melody, the smoke of frankincense curls up from behind him. Tunisian food and wine, the spice of sauces lingers on my palate as I sip the harsh red liquid, my mouth sings of these tastes, strange, exciting, luscious. We are shown the building; it was the home of a man who had many wives; rooms lead from the central corridor, each woman had a bedroom filled embroidered cloths and feathers, mosaics on the floor and tapestries on the walls. A larger room in which there is a wide bed is the conjugal space, shared, but never for long. I lie back on the bed and imagine that I am the favourite, I laugh with my riches.

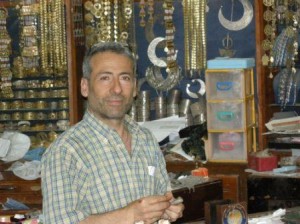

The following day we walk the souk. “Too much of this can make you souked –out,” I say to Tamiko. “I have experienced the entrepreneurial spirit of Morocco and Egypt, the endless streets and people who want to sell things to you. I love to walk them and talk to the people and bargain, but then I get tired.” We enter a small shop; the Bijouterie, all the shops are small, barely spaces to stand, strings of silver beads hang on the walls.

“How much are these beads,” Tamiko asks?

“Forty dinar,” a man replies, he is sleepy, he yawns as he sips an espresso.

“But this is expensive,” she replies, “I can get them for less in other places.”

“No,” the man with the bright white teeth and high cheek bones says, “these you cannot, they are special, they are Berber, made far away in a village at the edge of the desert. We have to get them here, we have to ask the people to come far to bring them to us. But any way I sell them by weight, so look, here I will weigh them and show you, then I will multiple the weight with the price of silver today. I will not cheat you.”

“Can I buy a few of them,” Tamiko asks, “I make jewellery and I want to use them for this jewellery, then I will sell them.”

“Wait here,” he replies, “I will call my brother, he is the one that does the main business. Wait, do you want coffee?”

I sit outside the shop and watch the people who walk by; women, most of them have intricately patterned head scarves and covered up arms, they walk in pairs, they look down, men with cigarettes and fruit, alone or together. Tamiko sits beside me, a man calls out a greeting in Arabic, “I think that they think I am Tunisian,” she says, ”the way I dress maybe, the colour of my skin? No-one harasses us, we don’t look like tourists.”

We wait, the bargaining begins, we wait some more, we haggle, we leave and promise to return …. strings of silver beads follow us. I buy a silver Hand of Fatima with a coral inlay to put above the doorway of my home; it will keep me safe for Fatima is the safe keeper of all homes.

But the medina is just a part of the city; the coast is dominated by hotels, white mausoleums that house the European holiday maker who know, and wants, to know little of the country, they lie on the sand and let the warm Mediterranean trickle over their toes and never imagine the violence and lusts of the past, the energy of traders selling their goods, the winding streets that tell a story. There are also the suburbs, modern Western houses, apartment blocks and administrative buildings, the site of government and commerce.

Tunis has many different parts that all reflect something, and always linked by the call to prayer, the sound of the muezzin. At midday every Friday the city bows to the earth, faces turn towards Mecca, bruises are imprinted on foreheads and all find solace in the true teachings of Mohammed.

Ten kilometres from Tunis is Carthage, Tunis was previously a satellite town to this warring universe, we take a train, a blue and white train ticket for less than a rand, ruins stretch along the coast, different eras reflected in the waves. I walk among crumbling stones, touch blue and white mosaics in vessels the size of a bath tub, ponder the smile on the face of a marble man, he stares across the water, wondering and dreaming of blood stained battles. I do not know archaeology, I cannot tell if the ruins of a building are Roman or those of Hannibal, I just look and wander and imagine stories from long ago. Carthage, a narrative of violence and war, lust and riches, strange rituals of child sacrifice to the great god Baal, Carthage, its powers rivalled even Rome. I take my book from my bag, Flaubert’s ‘Salammbo’, a true account of vastness or an orientalist fantasy; I do not judge but picture the high priestess of Punic rites who revelled in sexual sadism, cruelty and decadent luxury. I dream of romance; Dido, the Phoenician queen, waiting and watching the sea, her beloved Aeneus deserting her to fulfil Rome’s glorious destiny, her eventual suicide, her body in which there was a heart, a heart rend into two. And now there is nothing left of the rituals and the bloody tears, the Romans defeated the Carthaginians in the Punic wars, destroyed the city and built their structures on top of the rubble; Hannibal no longer lurked outside the gates. An elderly Japanese woman, her face porcelain, walks with a cane that makes a footprint, she is with a guide, he speaks to her in Japanese and tells her of Aphrodite and Venus, Mars and Jupiter, love, war, beauty and violence. She looks with respect at fragmented walls and imagines that she is a woman watching the sea as she washes the feet of her husband, her soldier.

Ten kilometres from Tunis is Carthage, Tunis was previously a satellite town to this warring universe, we take a train, a blue and white train ticket for less than a rand, ruins stretch along the coast, different eras reflected in the waves. I walk among crumbling stones, touch blue and white mosaics in vessels the size of a bath tub, ponder the smile on the face of a marble man, he stares across the water, wondering and dreaming of blood stained battles. I do not know archaeology, I cannot tell if the ruins of a building are Roman or those of Hannibal, I just look and wander and imagine stories from long ago. Carthage, a narrative of violence and war, lust and riches, strange rituals of child sacrifice to the great god Baal, Carthage, its powers rivalled even Rome. I take my book from my bag, Flaubert’s ‘Salammbo’, a true account of vastness or an orientalist fantasy; I do not judge but picture the high priestess of Punic rites who revelled in sexual sadism, cruelty and decadent luxury. I dream of romance; Dido, the Phoenician queen, waiting and watching the sea, her beloved Aeneus deserting her to fulfil Rome’s glorious destiny, her eventual suicide, her body in which there was a heart, a heart rend into two. And now there is nothing left of the rituals and the bloody tears, the Romans defeated the Carthaginians in the Punic wars, destroyed the city and built their structures on top of the rubble; Hannibal no longer lurked outside the gates. An elderly Japanese woman, her face porcelain, walks with a cane that makes a footprint, she is with a guide, he speaks to her in Japanese and tells her of Aphrodite and Venus, Mars and Jupiter, love, war, beauty and violence. She looks with respect at fragmented walls and imagines that she is a woman watching the sea as she washes the feet of her husband, her soldier.

And today, while it borders onto Algeria and Libya, Tunisia has none of the fierceness associated with the past or of these countries, it is a place of calm, of trade and of tourism; the unruffled Mediterranean, the tides of blood.

We catch an aeroplane to Djerba Island, here it is cool, there is no humidity. I feel the gods look at me as I step onto the tarmac for legend has it that Djerba was the island of the Lotus-Eaters. Here Odysseus, stranded on his voyage through the Mediterranean on his way home to his faithful Penelope after twenty years of the Trojan war, in the voice of Homer said; “I was driven thence by foul winds for a space of nine days upon the sea, but on the tenth day we reached the land of the Lotus-eaters, who live on a food that comes from a kind of flower …… the Lotus-Eaters, men who did them no hurt, but gave them to eat of the lotus, which was so delicious that those who ate of it left off caring about home, without thinking further of their return; nevertheless, though they wept bitterly I forced them back to the ships and made them fast under the benches ….. so they took their places and smote the grey sea with their oars.”

We stay in an old building which has become a guest house in Houmt-Souk, the largest and oldest of Djerba’s towns. In the evening I sit in the souk and drink freshly squeezed orange juice, I listen to the card playing men at the table next to me, an unfamiliar sound, the language does not accord with anything I know, Berber, for Djerba is one of the few remaining places in Tunisia where this language is still spoken. A taxi driver takes us on a tour of the island, it is small, easily navigable in a morning, a day if you want to meander through the small towns looking at pottery or pick your way along the coast through old Roman ruins which lie on the shoreline, the past, history, always told, never revealed.

The people of Tunisia are, in the main, Muslim, however Djerba is noted for its Jewish and Catholic communities. The Jews have lived on the island for more than 2500 years and while the population has lessened die to emigration, they are still here. We visit the synagogue, it is closely guarded, my bag through the X-ray machine, I walk the closed walls and watch old men intone their prayers to the lord, and in the sacred space of books and holiness, if I close my eye I would not know what language they chant or what religion they sing for. They sing to a God, my God, your God, all our Gods.

In Houmt Souk we walk through the souk; carpets, jewellery, pottery, chocolate, silverware; expensive and cheap side by side, a stall with old silver beads next to a tourist jewellery shop where fine necklaces and bracelets adorn the glass shelves. As we ask about beads, by now we realise that some are made to look antique, ‘ancien’, we begin to know which are the older and which have been newly made. Most of the beads are silver, or silver plated; a Berber bead, for it is a Berber town.

We stop at a shop, Bittan – La Coupole, the man who approaches us says, “my family, we are Jewish, have lived on the island for many years, I do not know anything else; Tunisia, that is the continent, here we are islanders.”

We stop at a shop, Bittan – La Coupole, the man who approaches us says, “my family, we are Jewish, have lived on the island for many years, I do not know anything else; Tunisia, that is the continent, here we are islanders.”

We look around; there are beads everywhere, Hands of Fatima, turquoise stones, filigree sliver bracelets, gold necklaces, brass and copper incense urns.

We look around; there are beads everywhere, Hands of Fatima, turquoise stones, filigree sliver bracelets, gold necklaces, brass and copper incense urns.

“Pick out the ones that you want,” the man says as he turns to another customer, a woman who is choosing an engagement ring, he takes a box from beneath the counter, expensive, then he returns to us. “Choose,” he continues, “I will weigh them, look there is the price of silver, I listen to the radio everyday so I know what it is, how it fluctuates, today, yes you are lucky the price is down.” He laughs for he knows that we do not know what the price of silver is, but he is charming. “Come, what do you like,” he asks?

The woman puts a ring on her finger, watches her hand in the mirror and dreams of lying pressed to her husband’s skin, hennaed hands with a ring caress hope.

We look and choose, making pictures of a necklace, a bracelet, a celebration, and all the while the shop’s owner looks and moves, looks and advises, laughs. After a long while we have chosen, he picks up a bead, and weighs it, then another, then another, calculating the price in relation to the price of silver.

This is more than we anticipated, and so we bargain. I do not know trade, the art of the bargain, so I put two beads aside “….. not these, well maybe if you can give it to me for …… and these no they are way too expensive.” I laugh for I know that he will make a handsome profit on the sale.

We walk to the door, he watches us, I loiter outside.

“Wait here,” Tamiko says, “I want to buy some of that nougat,” she points to a low wooden table on which a mound of the fresh honey scented sweet lies.

“Come inside,” he says, “we can make an arrangement. I have to keep this shop going,” he continues, “sometimes business is good, sometimes no, I will make you a very good price maybe we can work something out.”

We come away with packets of beads; silver, ornate, decoration for long necks and pale wrists, exquisitely delighted.

Then we move onto Sidi Bou Said. This town is not very far from Tunis, similar, yet different. It is turquoise and yellow; yellow wooden doors mark secret entrances to walled houses, sapphire coloured windows frame faces and pink flowers. We stay in a guest house that is at the top of the old town, the taxi drive grumbles, “I am not allowed to go there,”he says, “no cars, wait I will ask?” He stops a policeman; there are many policemen in Tunisia, suave in television shows, cool blue jeans, white T-shirts, aviator sunglasses, smiling, menacing, friendly. We get permission to drive to the top, for some of the way we walk. In the heat of midday I sit outside the room in the middle courtyard; overhanging creepers touch my face, a turtle walks on the edge of a pond, it is cool. We sit and drink sweet mint tea as we rest.

“Let’s take a walk,” Tamiko says, “to look at the streets and the views, maybe a coffee?”

“Let’s take a walk,” Tamiko says, “to look at the streets and the views, maybe a coffee?”

We walk the cobbled streets, up the long winding hill, past markets that sell to tourists, a man that sells perfumed flowers gives us one for our hair, a smoking bar is on a rooftop is dark. In a restaurant we drink freshly squeezed juice and watch the bay, the bluer than cerulean sea, the ships on the water, the new and the old, the rich and the poor houses of the town. Far below the tourists board tour busses, they sweat as we do not for it is not the beach and the boredom that we want, we want the beads and the fun and the people of Tunisia. In the shops we negotiate, we wrangle, we wonder at everything that is ancient but new, we laugh and eat ice-cream and then, tired, stop at one of the many restaurants that line the road and eat sweet couscous and drink cold tea, for alcohol is forbidden in this Muslim town.

And as the sun goes down and the fresh breeze winds its way along the passages of time we look at the polished beads, they flash and glitter, they sparkle with stories and time. We watch the horizon, the ruins of the past, the up-to-the-minute future; we watch time itself, reality in the past and the silver stories that are beads.