Victoria Falls Zimbabwe

by Barbara on Mar.15, 2010, under Published Travel Articles

THUNDERING SPLENDID SMOKE

Sunday Independent, Victoria Falls July 2010

“Zimbabwe, are you going there?” a friend asks as we drink freshly roasted rich Zimbabwean coffee, “aren’t you a little bit nervous, what with all that is happening, and what about supporting a corrupt regime, how can you do it?”

“It’s the conundrum,” I reply, “only by going there will it normalise, only by not going will it normalise? And anyway I have always wanted to visit the Falls.”

And so I go; air ticket, hotel voucher for three nights, a boat trip on the Zambezi, all of this in one package, and for the price of one night in the Johannesburg Park Hyatt.

The road to the Victoria Falls Hotel is lonely, there are no trees, a vendor sits on the side of the road, there is no energy, just a bright sun. The hotel is white, thick walls set on high ground, below this a sloping watered lawn, a Gabar Goshawk drinks from a pond, a tall stone structure tells me that it is 6700 miles to Cairo, and beyond this there is mist, smoke billowing.

We follow the sign that says Victoria Falls. It takes us out of a small gate and away from the immaculate green garden into scrubby brown bush. On either side of the path the acacia trees lean inwards to catch the walker with their thorns. “Careful,” the guard tells us, “it has been reported that they are here today, somewhere in the trees, and you can’t really see them unless you almost walk into them they are so good at disguise.”

I immediately think of bandits, this is a poor country, people are hungry.

“Sometimes on this path you come across elephants,” he continues, “they are very big and can be dangerous, so be very careful.”

We walk, the path is uneven, I kick a stone. Out of the bush emerge young boys; they are holding elephants, rhinoceroses, dollars …..

“We are hungry …,” “Please buy something….” “Twenty Rand…”

One young boy shows me beautifully carved animals, flowery bowls that have no scratch, smooth, another shows me a bank note, five hundred trillion dollars, a walking stick.

All around us these young men materialise, they are not threatening, they just want to sell something, their eyes are hungry. It’s like running the gauntlet but without the danger, I do not feel threatened, only assailed.

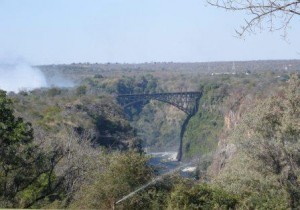

We walk across a road that leads to the Falls, then across the bridge that spans two countries, Zambia and Zimbabwe. I stand in ‘no mans land’ and watch the Zambezi River, a rainbow, the sun shafts through the mist. I feel cold water on my shoulders. Another young man approaches us. “I can make sure that you have a good time at the Falls,” he says, “I can show you that they are a world wonder.”

“I will go there tomorrow, I reply, “but tell me something about them?”

“Step over the railway line, feel the mist in your face,” he says, “do you know that Cecil John Rhodes, the Englishman who came here to make a lot of money, he built this railway line exactly at this point because he said that the white passengers, as they travelled the train all the way from Cape Town to Cairo, should look out of the window at the spray and feel it in their blinded eyes

I can feel the sound of the train as it thunders across the water, I imagine pink flushed delight.

We walk back, it is not far, but I have been walking for a long time. “Lets stop and have a coke,” I say to my friend, “coke, the ubiquitous drink that you can buy anywhere despite poverty, cultural difference, language, coke is always available.”

A vendor stands next to the taxi drivers, rusted cars. I take out a tobacco pouch and prepare a cigarette, a driver watches me. “What are you doing,” he says?

“I am making a cigarette, I say.

He puts his own cigarette to his lips, “interesting,” he laughs.

I make him a cigarette and give it to him. Another man approaches us, “buy some dollars,” he calls, “thirty billion for only one US.”

I turn to the man who is selling the coke, “how much is a coke,” I ask him?

“One US dollar,” he replies.

“If I give a dollar to this man,” I point to the man who wants to swap thirty trillion dollars, “will you take thirty trillion for a coke?”

He laughs, “no,” he says, “now we only take SA Rands and US dollars.”

“Sorry,” I turn to the money seller, “I want a coke and he will not take that money.”

I am tired, so we ask the smoking taxi driver to take us back to the hotel. “Four US,” he says and laughs again, he knows that we will pay the price as we are tired, the day has been long.

The Victoria Falls Hotel: a decaying opulence, a time warp, as I walk down the long wide corridor to my room I feel as if I have been transported backwards into a colonial time. I look at the pictures on the walls, old pink coloured maps show the explorers, footsteps of Europe: Stanley at the Falls points northwards, he is discovering something new, something that no man has ever travelled to, for all men are European, none can be African, they are natives, people to conquer and barter with, a picture of Queen Mary and King Edward VII, the adolescent princesses stand at their side, the now queen of mighty England looks bemused and hot, her white dress cannot disguise the drops of water on her breasts, she glows, the native porter who stands nearby with a portmanteau and a fan sweats. The bedroom is large, a wide bed on the one side and thick brocade curtains that hide the sumptuous gardens below, a chocolate waits for me on the pillow, the only glimpse I have of the twenty first century is a television set on which CNN plays, it shows war, the ravages of a wasteland. I walk inside the bathroom, the soap is thick and orange, the tap that I turn on is solid brass, black and white tiles under my feet.

We walk to the Stanley Bar. “Let’s have a cocktail,” I say, “this is the kind of place where you drink cocktails.” Above the bar is a picture of Stanley, his foot rests on the wide neck of an elephant, his rifle lies across his shoulders, two native porters carry long ivory tusks, blood seeps from the elephant’s wounds, it is craven. The barman, who is dressed in black and white, asks us what we would like. I look at the cocktail menu, mango martini, sweet chilli chocolate rum, mint jellup, the list goes on. “I think a mango martini is what I want,” I laugh, “in Africa martini is made with mangos, not olives.” As I sip the beautiful taste and feel my head grow lighter I watch the waiters outside on the veranda. All wear white gloves, they laugh politely; they serve as if ordained by God.

We walk around the hotel and into the Livingstone Room, already the frogs are beginning to sing from the pond outside, it is a melody that is both melancholy and joyful.

“Would you like to dine here tonight,” the maitre’d asks us? “My name is Phillip, where do you come from?”

“South Africa,” my friend replies.

“Ah,” he says, “my children are both there, the one is at the University of Johannesburg studying engineering and the other is in Polokwane studying marketing. I never speak to them; children don’t talk to fathers much do they? But come I will show you to your table.”

The restaurant is bigger than three small Johannesburg homes, in its centre is a dance floor, a man sits at a piano and plays jazz sounds. There is no-one inside it but us. The table is immaculate, the serviettes are so starched that as I pick one up to wipe a finger it crackles, the wine glasses are in the correct places and the heavy pewter cutlery is just the right distance apart.

“What can I get you, here is the menu, we do not have the tilapia today, we could not get it fresh so it has not been prepared, but we have the Zambezi perch. We do not have our Zimbabwean wine either, guests do not like it, it is too rough, so try a South African one, oh I forgot you drink this all the time, well try it anyway.”

And no-one comes into the restaurant, we are the only guests. “I think that this is where a celebration should be held,” I say to my friend, “the tango on the dance floor, guests that you have to run a marathon to get to, a piano player playing long gone songs.” And the piano player plays for us, for two hours he does not stop, he plays as if the audience was twenty five thousand strong, he plays because he plays.

The next day the hotel fills up. The Common Market of Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) conference is being held nearby. Heads of state, body guards with ear pieces and sunglasses, delegates from Libya, Kenya Sudan, Ethiopia …. There is no South African delegation; the new colonists have not joined the organisation. Men in black suits alight from Mercedes Benz’s, mobile phones held to ears, women in strong African designs. The elegant colonial grace of yesterday and the bemused free Africa today; an acceptance of history, it happened, it cannot be erased.

The next day we walk the gauntlet, and what did not prey on us the day before is here today. Three elephants cross the path; one reaches lazily into the acacia thorns and twists off a branch, another blows its trumpet and another just stares at us. I am afraid to pass them. A man with a bag over his shoulder approaches, “they are not dangerous,” he says, “unless one steps on you,” he laughs, “today just walk by, they are doing what they do and you are doing what you do.” I am silent and afraid, but the elephant do not care, they lackadaisically enjoy breakfast.

At the entrance to the Falls two men approach us, “you will get wet, it is very wet down there,” one says, “here buy a rain coat.” Two tourists emerge from the park gates, they are sodden. “Two for two dollars,” he says.

The Victoria Falls stretches for 1.6 kilometres on the Zimbabwean side and 0.6 kilometres on the Zambian side. On the Zambian side it is short and dangerous, water and slippery bridges, on the Zimbabwean side it is elongated, winding paths are manicured, rain forest birds dart. The Falls are not describable, there are no words that can tell their magnificence, wide, long, deep, blue and green, rainbows, green trees appear and disappear in the mist. Is this the place to die in, I wonder, if I had a terminal disease what bliss to slip over the barrier and be swept away by the smoke that thunders.

After four hours of wondering and wandering and getting wet and sitting in the sun to dry and then getting wet again we leave. I am happy; there is something bigger than me, a mystery.

Outside we walk past the taxi drivers, again I am tired, the driver who charged us four dollars the day before smiles at me. “Want a ride,” he asks?

“We have no more money,” my friend says, for we only have a hundred dollar note which must last another day.

“Hey don’t worry, today you can have the ride for free,” he says, “this is Africa, today I charge tomorrow I don’t.”