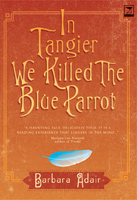

In Tangier We Killed the Blue Parrot

by Barbara on Jun.16, 2009, under Published Novels and Short Stories

IN TANGIER WE KILLED THE BLUE PARROT – A NOVEL BY BARBARA ADAIR

Shortlisted for the Sunday Times Fiction Award – 2005

SUMMARY

In Tangier we Killed the Blue Parrot is a novel set in Morocco in the 1940s and weaves a story around the well-known writers, Paul and Jane Bowles. Paul was a composer and author of The Sheltering Sky, and Jane was the author of Two Serious Ladies.

This mesmerising novel draws the reader into the creative, erotic and exiled minds of Paul and Jane Bowles. Their struggles to write and their struggle to love, both each other and others, creates an unusually rich experience for the reader, and one which is hard to forget.

‘A haunting tale, delicately told. Adair has done an impressive amount of research to lay bare the underbelly of authorial fame. Writerly narcissism, betrayal, moral confusion, love, lust and loss are the themes developed here in the context of the historical foray of Jane and Paul Bowles into Morocco. It is a reading experience that lingers in the mind through the quiet but compelling depictions of artistic grandiosity, hubris and despair set against a backdrop of power struggles in dysfunctional relationships and against the weft of politics and an economy of survival in a developing country. Hard questions about the ethics of writing and authorship in any comparable situation clearly inform this narrative and lends a self-reflexive depth to all the voices that Adair so skillfully evokes for her purpose. Yet it also leaves the reader with an overbearing sense of melancholy and sadness about the (unavoidable ?) traps of desire and exoticism that any western writer confronting any ” other” will encounter.’ – Marlene van Niekerk JACANA MEDIA

The First Chapter

Belquassim leaned forward and took a sip from the glass he held in his right hand. He did not usually drink alcohol, which was prohibited to him. But on this occasion, recalling events that had long passed, he needed to drink from a cup of fierce fiery yellow liquid. He raised the glass, To Paul and Jane, he whispered to himself. Strange,… he thought. Memories are remembered so that the adventure can be told. The telling of a memory makes the story, the story that is more exotic than the experience. What happened itself is not real, only the story is real. The real adventure. And it can never be repeated. And he had never told this story before.

From down the bar a woman laughed. The bar was in the Hotel Mirador. In room 35 there was a painting on the wall over the bed. The story was that Matisse had painted it when he was visiting Tangier with Madame Matisse, before he was famous. Belquassim remembered how the hotel employees were always quick to tell anyone who looked like a tourist that Henri Matisse and his wife and, of course, Gertrude and Alice, had stayed in the Hotel Mirador. And, for a small fee, guests could go into the room and look at the painting. For a somewhat larger fee guests could sleep the night under the colours of this revered artist. But really – and Belquassim knew this because he had been into room 35 and Paul had shown him some photographs of the now famous artist’s work – the wall just had a few different colours added to it by the painter. A few colours added to the stains of the rust and the damp. Matisse must have been thinking of other things as he splashed his paint across the wall above the bed. Who could tell now? Belquassim wondered if the colours were still there, or if they had been painted over by the new hotel proprietor, who did not know of Matisse, and was unaware of how the history of art had pervaded the walls of the Hotel Mirador. Belquassim wondered if the proprietor had painted the wall a bright white to show how clean it was.

Paul had taught him everything about Matisse and the Parisian painters, he reflected. What had he said? “They tried to express their unconscious desires on canvas. The unconscious is like a Cubist painting. It has no discernible pattern. Straight lines, but they are not linear.” Paul also said, “And Gertrude…. She loved collecting the new Paris art. She accumulated sentences and she made art.” What had Paul meant by this? How could she collect sentences? Sentences could not be held in a hand, touched, caressed. But he remembered Paul saying that he caressed sentences. Belquassim would watch him when he held a pen. What did he mean? Belquassim remembered Paul’s pale white beautiful face and his cold blue eyes, and his voice, soft and gentle and menacing. Everything that he knew had come from Paul: the world, music, poetry, philosophy and love.

Behind the bar were rows of bottles on shelves. Behind the bottles was a painted picture. Blue headed Touregs on camels racing through the desert. A tourist picture. A picture those tourists drew of Morocco. Fierce faced camel riders dressed in blue. The bar was dark. The bottles on the shelves and the stained picture behind them were lit up by a single bare globe. The picture could barely be seen, just as no Touregs could be seen in Tangier. It was as if it was night. But if Belquassim turned on his stool and looked across the shadowy room he could see the beach. Bright hard sunlight flickered over the long palm fronds that persistently blurred his view. He could see Madame Porte’s famous Salon de The, it was at the edge of beach, its red awnings moving in the breeze that blew in from the blue sea. The windows of the salon were closed, Madame Porte was no longer there. He wondered where she was. A seagull stood on the narrow wall that separated the salon from the beach. Its yellow feet clutched the wall, but it could not find a grip, these feet were not made for hard brickwork, they were webbed, meant for water, not walls. It swooped down into the waveless sea and then emerged again. Belquassim could see the shape of a fish in its beak. The curved sharp end plunged into the flesh of the fish. The fish was dead but Belquassim thought he could feel its pain. He could feel that beak slash through his flesh, damaging him, tearing him apart.

Belquassim remembered the long hours in this bar. He remembered the tea in the Salon. In these two places he would sit for hours listening to the chatter of the expatriates, the writers and the philosophers. He had learned a lot; a lot about despair and love and hatred, the wars in Europe, the quality of the hashish and opium that could be found in the city. Nothing had changed but the faces, and Madame Porte was gone now. Belquassim walked over to the window of the bar, it was smudged by the salty spray of the sea. He peered out and looked carefully across the water. On a fine day he knew that he could see the coast of Spain. He had never been to Spain. But he knew about the Spanish writer Cervantes. Paul had read extracts from this thick book to him in the evenings as they sat on the veranda of the house. The faithful and foolish Sancho Panza, who loved his master more than he loved himself. Don Quixote, the knight errant, the adventurer. The giants who were windmills. The dream of Dulcinea. Belquassim had never been outside Morocco, although sometimes he believed that he had travelled the world. Travelled through the stories told to him by Paul. Morocco was the world for him then, as it was now. A different world now, but the world anyway. He narrowed his eyes and looked out of the window again. If he looked hard enough maybe he would see Jane’s grave in Malaga. A grave without a headstone and without an inscription.

Belquassim walked back to the bar and sat down. He leant backwards on the barstool. A grave and this tacky bar, he thought. But – he bent his head towards the glass that he drank from – it is not like the bar of the old days in Tangier. The days when Tangier was still part of the International Zone. The old bars smelt of musk and opium, they had the odour of opulence, they reeked of the expatriates. If you sat in a bar for just five minutes you could hear a million languages, dream languages from far away; America. Now the space of the half-day seemed to reverberate with the loneliness that he felt inside him. It reverberated with the woman’s laugh. The faded sepia photographs lined through with smoke on the walls were all that was left of that world. The woman smiled at him. White teeth stained with nicotine and red lipstick. For a moment he thought she seemed interested in him, but then she turned to her companion and laughed again. Her purple shirt stuck to her flat chest. The sweat of the city whitened her body. She reminded him of Jane, half-drunk, half-lovely. He wondered what he would do if she came over to him. He could not touch her as he had touched Jane. He could not brush her hair. It would not be the same. He could remember Jane’s skin, soft and milky, a girl’s skin. Sometimes on that white would appear a dimpled rash, pink spots marring the thin skin. The music from the radio echoed outside his head as he watched the woman get up; slowly she moved her thin body and started to beat time with her shoes. Time seems to have gone so quickly, he thought. And what was this music? had he heard it before? Maybe, but that was long ago. It sounded like the music that Paul had searched for in the mountains. Unrecorded Moroccan sounds. Now they played it on the radio.

Belquassim tried not to be angry. “Anger,” Paul had said, “like jealousy, is a wasted emotion. It takes a person nowhere. It is a waste of time and energy that could be spent differently. If you are angry it means that you care. And I have never cared enough to become angry.” Belquassim remembered Paul looking at him with his blue eyes as he spoke these words. ”Maybe I do care,” Paul continued, “I think I may care a little about beauty. But even that, if it were not here for me to look at I could not get angry. I will just describe beauty in my words if this happens.” And even though Belquassim tried not to feel anger, and not to feel jealousy, he could not suppress it. Anger and jealousy, a waste of time and energy. They showed that he cared. And he had nothing else to do with his time or energy. He continued to feel. But Paul was right, it was of no use; he could feel anger and he could feel jealously until it burst inside his head. Exploded like an orange smashed against the concrete beachfront pathway. The juice shooting upwards into the air. The segments scattering. And then things would be just the same again. People would walk over the orange segments without even seeing them. And things had felt just the same for a long time now.

Belquassim was thirty-five. He had lived his whole life in Tangier. He could remember the incipient stages of the writers’ and artists’ movement. He had seen the quixotic idealism of the transient residents, their decadence; their drugs and their loves grow up around him. How he loved that life. He loved the lack of morality, he loved the abandonment and he loved to watch. He had watched from the sidelines mostly, or at least until he had met Paul. He saw how people reached out and took whatever they could to pleasure themselves. He loved being an object of that love and that pleasure. It had seemed to him that whatever they, the expatriates, did they could change the world. But now he knew that they had not changed the world, they had only changed his world.

Paul and Jane had changed his world as they had changed their own world. They had freed themselves from the slow decay of social bondage. Freed themselves from prejudice, tyranny and despair. And yet where were they now?

After meeting Paul and his wife, Jane, Belquassim had begun to believe that even he and his world mattered and had meaning, and that he could belong in the life they showed him. Even he could be free. This was a world that was open to everyone. But those doors had closed now. A world open to everyone, but not any more. He had come so close to living a dream, this world and this life. He could touch it. He could feel it. He could smell it. And Paul had fostered his belief. He was in the constant presence of a dream. He remembered Paul saying, “A writer – for I am a writer now – does not try to escape from reality, he tries to change it so that he can escape from the limits of reality. Don’t credit me with this observation,” he had added. “It comes from Bill. And Bill has no reality. He has changed it, in his work and in the way he lives.” And Belquassim had escaped the limits, he had pushed the limits, and for a short time it seemed as if he had won. They had all escaped. But now, bound by his life he knew that that long sleep was over. The dream was over. He was awake now.

Belquassim remembered that Paul told him about Europe, about America, about a life that seemed so far away from the sun-bleached houses that overlooked the sea in Tangier. He remembered little of what these stories were about, he just remembered wanting to go to these faraway places. He remembered Paul promising to show him the high-rise buildings of New York City. And in return Belquassim told Paul about his country. Stories of his family, the stories his grandfather used to tell him about the caravans that sped across the desert, the hard leather of the bags tied to the sides of the camels loaded with silver and spices. Cracked Bedouin hands. Eyes that could see very little because of the hard sand that blew. The tracks across the desert that only one who has been there before can follow; scars across the landscape. The smell of the Hamatan – but even this hot wind that blows up the dust cannot erase the scars of the wounded. Pictures of the donkey caravan, in the sand the tiny hoofprints, moving in one direction, a donkey highway. Heavy slabs of salt taken from the salt pans. The endless journeys across so much space. Belquassim remembered how Paul loved these stories. From this he would fashion his own tales, tales of intrigue and passion. One world enjoined with another.

Paul had arrived in Tangier early. A long time before most of the other expatriates arrived. His wife, Jane, only came to the city later. Jane was a dark slight woman who appeared to be quite flighty. Paul said that she was not really flighty, she was as gifted an artist as he was, but she had somehow become stuck. Perhaps she had become stuck because of too much pleasure, Belquassim used to think. But now he knew that taking pleasure was the way in which she could become brave. She tried to define herself in pleasure. It was the way that she kept herself safe from those she most loved. How she kept safe from an outside world that she believed sought to judge her. Jane spent most of her time, when she was in Tangier, in the souks, constantly exploring another way, her lame leg stiff and unbending. She walked with a limp, unable to bend her right knee. Belquassim would watch her as she walked down the stairs of the house. Her left shoulder would fall downwards as she picked up her right leg and placed it carefully on the next step.

He remembered the story she had told him, the story of how her knee became stiff. “When I was a child,” she said,” I became very ill, some sort of wasting disease. My whole body collapsed, it was limp, as if I had no bones. I was like a jellyfish. And when I became well again my right leg was bent and could no longer move.” And then she laughed. He remembered the expression on her face when she told him how her mother had taken her to a doctor and how the doctor had straightened her leg. Her words lingered next to him. “All I remember is that I knew that I was vulnerable. You know how we all think that we are vulnerable, but we never think that this is real. It is a sort of contradiction: vulnerable but invulnerable. But after my leg that feeling of invulnerability disappeared. I was no longer brave. I knew that things could happen. I sort of often think about it. The before and the after. The brave me and the cowardly me.”

Jane had even learnt how to speak Moghrebi. She had persuaded herself that she was in love with a woman who sold herbs and other medicines in the market. Her name was Cherifa. Cherifa, tall, heavy and dark. She would cover herself with a jellaba and haik during the day. At home, in the evenings, she would wear a white cotton shirt and faded blue jeans. Her long brown fingers that she used to sift the millet, the long dark fingers that took Jane in the night. Belquassim imagined how they penetrated Jane’s body, a knife through her thin chest, a chest that would not be hard to pierce. Cherifa, an old woman now, still sat in the same place in the market, surrounded by young girls. Still sifting the millet with her fingers. Still using the same fingers in the black nights. Cherifa had wished that Jane would die, and that had come true. Was the die cast by her spells?

Jane was so fragile, so indulgent and so stoned, it seemed as if she could die at any moment. Cherifa wanted Jane to die, or so he was told. Cherifa wanted the house that she sometimes lived in with Jane. Belquassim had seen some of the talismans that Cherifa had given Jane, talismans made by sorcerers. The necklace made of the parrot feathers that Jane had hung on a leather cord and which she sometimes wore around her neck. Yellow and green feathers fluttering on her chest bones. The piece of cloth stolen from the sacred tomb of one of the saints, he could not remember which one. She had kept this material next to her bed, next to the first edition of Paul’s book. A dirty piece of brown cloth that was sacred and dangerous. He remembered the inscription that Paul had written on the front page of the book, ‘To Jane. P.B.’

Belquassim remembered Jane. He had not wanted her to die, and to die so far away from what she loved.

“I met you just in time” Paul often said. “Just in time for my writing to settle. Just in time for me to see the words, to love the words.” And the words were all that Paul loved. Paul had found him just in time, Belquassim liked that line. He had liked it because it gave him a sense that Paul needed him, needed him, if not for his love, then at least as an inspiration. Belquassim enabled Paul to write, he had thought that he gave Paul all his ideas, but all he had given him was his name. And Paul was still a writer, he still wrote words now. He remembered exactly when Paul had told him that he needed him. It was a Monday, in 1949. They were both walking out of the house where he and Belquassim, and sometimes Jane and dark haired Cherifa, lived. The house was right in the middle of the winding streets of the old dissolute part of the city, a part of the city that tourists rarely visited. The house near the Petit Socca. On that day Paul had been unable to find his way through the streets to the Café Hafa, his favourite café that overlooked the city and the beach. Belquassim had to show him where to go, which streets to follow, what to look out for along the way. He liked this feeling. He liked to show Paul where to go. Just as he liked to tell Paul his stories, just as he liked to listen. He thought he was indispensable.

Paul had come to Tangier to write music and to tape the indigenous music of the country, but he had ended up writing books and stories. Belquassim remembered Paul playing him some of the music that he had written for an opera. The story of a city and a life in it. A story that was written by a friend of his. He wrote music for his friends. As Belquassim sat in the study of the house where the gramophone was he remembered that he could hear in the record the perfumed explosion of the trumpet, that perfect explosion of pain. The pain that he now knew was his relationship with Paul. Pain so beautiful, the pain that his body wanted so much. The needle would hiss over the vinyl, scratching the black skin. Paul’s music set out a story that could not be described in words, it could never be told. But even though Belquassim loved the music more than the stories, he knew that Paul’s needed his words. His stories were like pictures created by hashish, they painted him into an unknown world of raw emotion that he had never recognised or known existed. Only his characters knew of this emotion, but even they were unable to recognise it. And Paul, he thought, wrote better than Jane did. Her stories were always filled with hope, whereas Paul’s words were richer, darker, evil. Paul would often say, ”’I write about space, emotional space, and the desert, with its cold dust and careless sun. The desert,” Paul had continued, “was just the right image for this emotional space. The vacuum of humanness, the depletion of anything that resembled meaning or morality. The desert has no rules.” Belquassim had not thought so then, but he had not contradicted Paul. He still did not think so. The desert, for him, captured an emptiness that was full of something other than that which was human. It had no human values. It represented a meaning that could not be duplicated or identified in people. Maybe it was God, so vast, so unconquerable, and yet so beautiful. The desert had no man-made rules. It had no rules imposed on it, but had created its own rules. Rules made of nothing but the sun and the sand. Rules that meant a lot.

He looked out again through the long fronted windows that were open to the ground. The outer humid sea air crept sluggishly up and into him. It seemed to dissipate his anger. Remembering brought him some comfort. The comfort of being older, no longer the in-love and loved young boy, but the older man, angry and jealous, but with an inner recognition of this condition. Suffering, he thought, is just about being alive. The immediacy of my own suffering, maybe, helps me to see the world more clearly. If I know about pain then at least I can know the pain of others. Maybe it will allow me to forgive more easily as I will know that everyone else suffers in much the same way as I do. Maybe this is what he had tried to explain to Paul about the desert. It enabled you to see, it enabled you to thirst for something more, but to forgive those who could not give it to you. But Paul had only been able to see what he wanted to see, everything else remained outside him, cold and distant, dark and unforgiving. Yet Belquassim knew that he had chosen this dark and unforgiving man. He could have walked on, he could have left him after the first night. But instead he had chosen to follow him, and it was the fact that he followed Paul that made him feel alive, the pain of life.